A couple of recent comments by my blogging friends have led me to think about the work of an actor/writer/director whose comic films I generally love--although a couple of his more recent works have not been up to his standards, plus he is just slightly more productive than Terence Malick. The first comment was by

Muffy St. Bernard in our discussion about "The Up Series" below. She talked about reality TV and its hunger for ever-more "interesting" subjects. The other comment was

thinkulous's entry about the evolutionary drive for humans to develop "big brains."

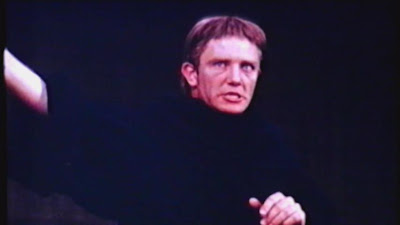

The name that immediately came to mind was Albert Brooks, and since

56 Up will probably be released before his next auteur effort, I figured I'd better write about him now, while we're both still alive, instead of waiting for his next film to come out.

Brooks's first directorial effort was

Real Life (1979), a riff on the attempt by PBS to produce the first serious "reality" series

, An American Family (1973). Brooks and a film crew set out to record a year in the life of a family. "And it's real!" as he yells at the end. This movie revealed how closely Brooks mined the border between the comedic and the discomforting: that what is humorous, if dialed up a notch, becomes disquieting, unsettling and embarassing.

A Modern Romance (1981) was Brooks's second movie as director, and I find it characteristically alternately hilarious and painful to watch--often in the same scene. Brooks's character is chronically jealous, which leads to some hilarious situations that teeter along the edge of, and by the end of the movie fall into, pathology. It's funny, but since we like his character, we don't want to watch him cause his romance to implode. The movie has a hilarious scene in which Brooks, whose character is a movie editor, works with the late Bruno Kirby on adding foley effects to a cheesy sf movie starring George Kennedy. I use it in my movie classes to illustrate how some foley effects are added to a movie, and besides doing that, it always gets some good laughs.

Defending Your Life is my favorite of Brooks's work. The central conceit--that the afterlife is like one huge, perfect time-share vacation spot where you await your assignment to your next life--is ingenious and affords an opportunity for satire on all sorts of levels. It's here that the "big brains" come in. Brooks's life on earth is defended by Rip Torn, who plays a more evolved creature who uses more of his brain--47%, vs. 3-5% by humans. We humans are thus called "little brains." In one scene, Brooks's character is eating a heaping plate of delicious food--none of which will make him heavy, or fill him up. Torn's character has a plate with a small amount of what appears to be burnt corned-beef hash.

Brooks: What are you eating?

Torn: You wouldn't like this.

Brooks: What is it? What does it taste like?

Torn: You're curious, aren't you? Good, I like that about you. You wanna try it?

Brooks: Yeah. (

Reaches over and takes a forkful.) Looks so weird. (

Puts it in his mouth and immediately spits it out in disgust).

Torn: (

Laughs).

Brooks: Oh, my God.

Torn: A little like horseshit, huh?

Brooks: (

Nods, with his napkin shoved over his mouth and audibly gulping with distaste).

Torn: As you get smarter, you begin to manipulate your senses. This tastes much different to me than it does to you.

Brooks: Eeeew. This is what

smart people eat?

Brooks's comedy is overt and sly at the same time. There's the gag, that smart people's food tastes horrible, and then there's the subtext--that smart people

like terrible things. Later, Brooks goes to a comedy club called "The Bomb Shelter." There, a smart comedian is making jokes about little brains, most of which are unfunny. When he asks Brooks, "How did you die?" Brooks answers, "On stage--like you." The audience laughs. Exactly

how smart are these people?

Brooks manages to thrust in another almost unbearably painful scene, during which he has to watch himself as a small child witness an argument between his parents. Most of the scenes replayed from his previous life have been funny: this knocks the breath out of you.

Brooks's next two films,

Mother and

The Muse, each have their moments, but are generally disappointing. His latest movie,

Looking for Comedy in the Muslim World, was generally panned, but I thought it was a return to much of his previous form. A joke on outsourcing requires the audience to pay attention to what is happening in the background of a scene, on two different occasions. Similarly, the main joke behind the comedy concert that Brooks gives contains several different layers, and takes time for the audience's realization of these layers to develop. This is the least unsettling of Brooks's movies, perhaps because of the potential for explosive adverse reaction if it became

too unsettling.

Albert Brooks's comedy takes patience, intelligence, and sensitivity to understand, and ususally provokes some thought afterwards. To think that he and Will Ferrell and Adam Sandler owe the same TV show their first big breaks.

"And it's

real!"

Added later: What makes those lines I quoted from

Defending Your Life charactertistically Brooksian is Torn's character saying, "You're curious, aren't you? Good, I like that about you." It adds nothing to the joke

per se, and it seems to make Torn into a nice guy, until we realize that he's (a) looking for anything that will buttress his defense of this loser, and (b) he's a condescending prat.